OUR 1984 TRIP TO THE USSR

OUR 1984 TRIP TO THE USSR

Recalling our harrowing tale 30 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain

By Rabbi Chaim Ingram OAM

(with the invaluable assistance of Mrs. Judith Ingram)

1.

Last week on 26th December, a landmark anniversary went almost unnoticed by the world. It marked exactly 30 years since the dramatic and unprecedented dissolution of the Former Soviet Union and its repressive and atheistic ideology. For seventy years, it held captive in its iron vice thousands of active dissidents including Jews many of whom were murdered, tortured and imprisoned for the crime of wishing to express their Judaism in the form of mitsva observance, education of their children or identification with Israel

In the manner of the ancient Greeks at the time of the Chanuka story, though even more brutally, the aim of Soviet Communism was to expunge any vestige of Judaism from the hearts of its citizens.

That it did not succeed, and that the proverbial Iron Curtain, seemingly impregnable, was lifted in such miraculous fashion late in 1991 is due to the grace of G-D and the spirit of its dissidents, in particular the valiant and self-sacrificing refuseniks – those Jews who refused to take “no” for an answer when submitting request after request to be allowed to make Aliya. In the 1970s and 1980s the cry of Moses “Let My People Go!” could be heard on the lips of banner-waving Jewish protesters throughout the Western world. Chief Rabbi Lord Jakobovits zl coined the variant slogan “Let My People Live!”

At the beginning of this year, I reproduced a sermon delivered in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK (where I had been assistant minister and chazan) in 1983 which led to Judith and I being selected by the local branch of the “35’s Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry” – what an amazing cadre of committed Jewish activists they were! – for a solidarity mission to the USSR to visit refuseniks in Leningrad and Moscow and to attempt to boost their spirits. This trip eventually took place in February 1984 at the height of the repression during the interregnum after Yuri Andropov’s death and prior to Konstantin Chernenko’s assuming power, at a time when the KGB were especially intent on proving to the new heads how effective they could be! Judith and I experienced a torrid time, being interrogated and held under house arrest by the KGB, an event which made the international media briefly. The resultant bad press it engendered for the KGB, having detained a rabbi and his wife for no illegal activity, actually improved the lot of the refuseniks for a while.

I promised at that time to tell the story in more detail later in the year. With the advent of thirty years since dissolution, no time is more appropriate than now. Amazingly I had never previously committed this story to writing. Judith and I had to dig deep into the recesses of our memories which we hope are reliable – and we found ourselves reliving the hashgacha p’ratit, the Divine Providence that we believe makes the story still worth telling almost forty years on.

********************

We were barely out of shana rishona, our first year of marriage. We were young and venturesome. It was nevertheless with some trepidation mingled with much excitement that we anticipated our ambassadorial trip behind the Iron Curtain.

We were professionally briefed as well as coached in the Cyrillic script and basic Russian words and phrases. Above all we were made aware of the fact that we were entering a repressive country at an immensely challenging time and that we had to maintain a balance between visiting the maximum number of refuseniks and staying safe and discreet.

We were given the names and addresses of three (maybe four) refuseniks in Leningrad and another three in Moscow. For our seven-day trip, we were to fly Aeroflot (the Soviet airline) to Leningrad on the Monday, stay till the Thursday then fly to Moscow where we would also spend Shabbat before flying home.

We had two suitcases and three bags, all of them bulging. (Thus began the Ingram tradition of always travelling with five pieces of protuberant luggage!) Their contents included: cosmetics (for refuseniks in prison to use as bribes to make life easier for them) and essential medications including Panadol and antibiotics (scarcely available in the USSR); clothes; sheitels; mezuzot (well-hidden in the depths of Judith’s capacious handbag); a small Megila; cassette tapes and a tiny cassette recorder (more on those later); and half a dozen sefarim, Jewish books ostensibly for our own use (we didn’t dare take more) but, in reality, to be given away. In addition, our cases contained our own vestiary requirements including heavy jumpers, given the sub-zero late-February conditions in Russia, and moon boots to navigate the snow – and our essential kosher food as well as my own tallit, tefillin and mini-siddur.

The names and addresses of the people we were to visit plus essential information were sequestered in code in my notebook. We were ready to fly!

We kept our heads down on the plane. I was wearing a flat cap and did not at all look like a rabbi. That didn’t stop one individual whom I sensed was a fellow-member of the tribe sidling up to me on the plane and trying to wheedle out of me what we were going to Leningrad for. I revealed nothing. We had been warned to trust nobody!

As we filed through passport control in Leningrad, we started to feel the tension as several airport bureaucrats (undoubtedly KGB agents) made a beeline for us. Of course, the Israeli stamps in our passports could not have helped. The titles of our books were noted down (we later discovered that they missed one which proved to be a veritable miracle, but more on that in due course!) and we were told we had better have them still with us when we departed the country. Our hearts sank. We wouldn’t be able to give them away as planned. All we could do is show them to the people we visited.

Our Mezuzot and Megila, thankfully, were not discovered. The bureaucrats did, however, request to listen to one of the cassette tapes. They seemed disappointed to hear the familiar and uncontroversial strains of Tchaikovsky’s music emanating from our recorder and shut it off after a few seconds. Had they had the patience to wait five minutes they would have heard the music cease and the sound of my voice recording a shiur on the laws of Shabbat. But mercifully, they didn’t! We thanked the Almighty for His kindness and in absentia our briefers for sharing with us their intelligent ploy!

An airport-hotel shuttle bus was waiting to take us to Hotel Leningrad (still operating, now called Hotel St. Petersburg). The other passengers bound for that hotel could have been forgiven for being irate at having to wait for us. Instead, they were concerned. A few muttered quietly to us how distressed they were at the way we had been singled out for “special treatment” at arrivals. That made us feel a little better!

On arrival at the hotel, our passports – together with those of our fellow-guests – were “held for safe keeping” (euphemism for “confiscated”). We arrived physically and mentally exhausted. Unfortunately, we slept through the meeting scheduled that evening at which we were expected to make our tours selection. This was a big mistake, due to which we never got to go on even one tour, as we had been advised we should. Our absence from all tours was assuredly noted by the surveillance agents who were everywhere. We were convinced that even the lifts were bugged! Judith and I had to be very careful even of what we said to each other, never mind to others, and when and where we said it!

Each floor was patrolled by a stern, unsmiling female commissar. She made sure we deposited our key whenever we left. It appeared her job was to monitor all the comings and goings and everything the guests said or did as well as to make the guests feel incredibly unwelcome and on edge!

The hotel was attractively situated by the water and near a naval museum. Later that evening, we went for a walk to get our bearings and to find a telephone box. Of course we didn’t dare to make any calls from the hotel. We succeeded in setting up our meetings with our designated Leningrad refuseniks. They were – we are thrilled we both still remember – Pavel Astrakhan, Yitzchak Kogan and Grigory Wasserman and their families. (It is possible there was a fourth, but we don’t recall.)

Pavel was a mechanical engineer, married to Sophia with a tiny daughter, Lily. (He was finally granted permission to emigrate in March 1987). I remember them as being very straightforward, sincere, salt-of-the-earth people. Yitzchak, known as the “Tsaddik of Leningrad”, was a baal teshuva who became a clandestine shochet. We remember him and his wife Sofa for their warm hospitality. We also recall him telling us how he always had to find a different site for his shechita operations lest he be caught in the act. He aided many refuseniks under the radar including “celebrities” like Ida Nudel and Iosef Mendelovitch. (He finally received permission to make aliya in 1986 but returned just before the fall of Communism to serve as a rabbi and mentor in Moscow where he now resides. His published autobiography in Hebrew tells his full, incredible life-story.)

Grigory (Zvi) Wasserman was a communications engineer with, I recall, a sharp and incisive intellect. He is now a charedi rabbi living in Rekhasim, near Haifa.

We were told inspirational stories about how Jews who only had a smidgen of Torah knowledge taught those who had none; and how valiant parents bound the right hand of their children in a bandage on Shabbat (Saturday school was compulsory) so that they would not have to write.

All the very special Jews we were privileged to meet expressed their deep appreciation for our visit. It means so much to know that Jews throughout the world care for our plight, they all said. What they did not realise is that they did far more for us than we for them! What we later experienced gave us a very small taste of the fear under which they lived on a daily basis. They were a tremendous beacon of continuing inspiration.

Grigory introduced us to his close circle of fellow-refuseniks. When it came out that I was a serving chazan, one of them, a musician, asked if she could arrange a concert in her home for the next evening, which was planned to be our last in Leningrad before flying on to Moscow.

I was only too happy to oblige. I was given to understand that there was nothing illegal in performing at a concert even if Jewish music was sung. This came under the banner of “Jewish culture” and was permitted – as long as there was no praying or textual study.

We had, by this point, deposited all the clothes, medicines, cosmetics, sheitels, tapes and mezuzot designated for Leningrad. We had not left behind any of the books as we knew we had to return with them. But after Judith got into discussion with one of the female refuseniks about taharat ha-mishpacha and mikveh, we agreed to leave a small booklet called A Guide To Family Purity (which Judith still had tucked in her handbag) behind, stipulating that we would need to pick it up the following evening from the home where the concert was to be held. This gave them an invaluable opportunity to photocopy the contents.

We had travelled by Metro to all of our destinations. But the following evening, as the place to which we were going was not accessible by Metro, for the first time, we took a taxi.

I shall never know whether that taxi driver suspected something about us or about where we were going and played informant. All I do know is that as we entered the building where the concert was to be held, we found ourselves surrounded by KGB agents who told us we were under arrest on the preposterous charge of harbouring narcotics. Later we found out this was merely a ploy to enable them to take us in a darkened vehicle to the police station for interrogation regarding a far darker crime – acting in a hostile fashion towards the State.

2.

With hindsight, we should not have been taken by surprise. Even when we were going for an innocent walk around the environs of Hotel Leningrad, Judith said she felt eyes staring at us. Once she turned around and was sure she saw in the distance four men sporting heavy Russian fur hats, one with a pair of binoculars pointed in our direction.

So it was that when we entered the building where I was to give a private concert to a small, invited group of proud Soviet Jews – which was perfectly permissible – we were surrounded by KGB agents and placed under arrest. The agents kept shouting “Narcotics, narcotics!” This was merely to intimidate us, as we later discovered. We were led into a darkened vehicle and driven to the local police headquarters.

There we were thoroughly searched. Of course, they found no incriminating evidence (only one loose Panadol). But they would not let us go, Instead, one of the KGB agents in a broken English accused us of acting in a hostile fashion towards the Soviet State.

When we inquired what exactly they meant, they were quite specific. They accused us of distributing “Zionist pamphlets and literature” to Soviet Jews.

This we were quite truthfully able to deny! We had come with no literature whatsoever about Israel. I replied: “We were seeking only to engage with our Jewish brothers and sisters, much as we do whenever we travel to cities with a Jewish population”.

Still, they persisted with the “Zionist” charge. They asked us if we were members of any Zionist organisation. Again, we were truthfully able to say “No!” (We had both once been members of youth Zionist groups but currently were not subscribed to any group specifically promoting Zionism.).

They were making no headway with us. Still, they were determined to embarrass us – and, in so doing, succeed in ingratiating themselves with the new President-elect for their strong-armed tactics in support of Soviet repressive ideals.

So they decided to blow their ‘story’ up in a big way – not that we realised at the time what was happening!

We were driven back to our hotel in the same cloak-and-dagger way we were picked up. Bizarrely, we were frogmarched across the foyer, much to the consternation of our fellow-guests (another part of their staged routine, though at the time it was extremely unnerving) and placed in the hotel interrogation room. (Apparently every major hotel in the USSR was ‘graced’ with a designated interrogation room ☹)

A journalist from Tass (the Soviet news agency) was there as well as our interrogator and also an interpreter/translator. Other officials stood by to further intimidate us.

We were yet again accused of hostile activity against the state and interrogated at length. The questions were variations ad nauseam on the same theme as those we had been asked at the police headquarters. The interrogation seemed to go on forever, but this was partly because of the time taken for each question to be asked, translated, responded to by us and noted down. It didn’t help their cause that the interpreter was having great difficulty in formulating the questions to us in English.

The One Above was truly with us, putting the right words into our mouths! We managed to keep calm and led them around in circles – to their great frustration. They were hoping to trip us up big time!

Eventually they realised they could get no more out of us. And so the psychological mind-games started. They told us we were under house arrest. We were free to go anywhere in the hotel but not step foot outside, until the “corridors of power” would decide what should be done with us.

This was late Wednesday evening – the 29th of February 1984. We had been due to fly to Moscow the following day. This would sadly no longer transpire. But that now had to be the least of our concerns.

Left alone in our rooms, the full impact of our situation hit us. We knew we had done nothing wrong. But we were in a repressive, immoral country which presently found itself without a leader. The KGB made up the rules as they went along!

There were peculiar contraptions hanging from the ceiling. We felt certain that the room was bugged. So whenever we spoke, we put the bathroom tap on full pelt. This drowned out our voices sufficiently!

I cannot remember much about that night, but I don’t think we slept much. I am sure I must have said fervent tehilim before retiring.

***********************

Morning dawned We comforted ourselves somewhat in that we knew our story would soon be public knowledge via Tass. The 35s and our community back home would learn of our situation and would surely be able to aid us in our plight

However, we knew we also had to help ourselves. Our briefers had given us the phone number of the British Embassy. We had no choice but to ring from the hotel telephone.

We spoke to an embassy official and advised her as dispassionately as we could of our plight, while being careful not to speak a word against the Soviet authorities. The Embassy official appeared very curt and said very little to encourage us. Our unease grew as the day wore on. It was not lessened by the continuous presence of a man just outside our window reading a newspaper (the same one) all day in the freezing weather. We felt sure he was there because of us – to ensure we did not try to leave the building. Not that we had any plans to. They held the cards – and our passports!

The day wore on. We still did not know what our fate would be. The tension mounted. We didn’t want to stay cooped up in our room playing Uno all day. We acted as normally and unobtrusively as possible. At one stage we made our way to the shops which were housed in the hotel complex and bought a white Russian fur hat (which I still call my streimel) and some other souvenirs. For a few blissful moments, we forgot that we were anything but run-of-the-mill tourists! We returned to our room. Still no word.

************************

Eventually as the day was waning, there was a rap on the door. We were taken down to an office where a large, poker-faced uniformed lady sitting behind an oversize imposing desk informed us imperiously that our visitors’ visas were being cancelled. She proceeded to slam a big stamp marked CANCELLED on our visa and handed us our passports. We ha a plane ticket from Moscow to London but that was no use to us. She told us we would need to take the first available plane to Helsinki (the nearest port outside the USSR) at our own expense. Credit card was unacceptable. Cash was the only commodity that would be accepted.

When told the price of the airfare to Helsinki, we told her, quite truthfully, that we did not have enough cash to cover it. Her response was that they would put us on a train. The train was due to leave the following morning. Friday. Erev Shabbos!

We quickly checked the departure time of the train, the duration of the trip and the time of sunset. We estimated that we would arrive in Helsinki with more than ninety minutes to spare before candle-lighting.

We were still in a daze. But at least we knew when and where we were bound. Our disappointment at not being able to visit our Moscow refuseniks were tempered with our longing to get out of that repressive country. However. we very concerned about the refuseniks we had met and hoped they were not being singled out for “treatment”. We continued to daven

In the morning, we were summoned early. We were escorted to one of a fleet of waiting Black Mariahs all of which drove away in consort at top speed with a loud screeching of tyres. It could have been a scene out of a James Bond movie. But we were the hapless leading ‘actors’ in a real-life drama of which we didn’t choose to be a part.

The tension did not lift when we boarded the train. We were assigned to a carriage by ourselves for which we were grateful. But we saw several authority-figures pass our carriage plus a few passengers. All looked as grim and as tense as we did.

And then we remembered something that increased our tension levels to new heights.

Among the books that the airport bureaucrats had listed was the Guide to Family Purity which we had loaned to the refuseniks, intending to retrieve it at the venue for the concert. But we were apprehended prior. So we didn’t have the book.

What sort of major drama were the KGB going to create over that? Would we be detained for more questioning? And then what? This time we had no defence! What were we going to do?

3.

As we sped from the hotel to the train station, we could not help noticing out of the window the multitudes of people lining up outside the food stores in the freezing cold, desperate to procure basic staples from the near-empty shelves, resignation writ large on their faces. This was our last and lasting impression of the Soviet “paradise”.

Our emotions were very mixed. We were, on the one hand, relieved to be leaving that benighted country. On the other hand. we felt the nagging weight of partial failure and of unfinished business (we had only seen half the refuseniks we had intended to see, although we also had some ‘bonus’ encounters) as well as deep concern for the Jews we had visited.

On the train, the realisation hit us that we were minus one of the books – A Guide To Family Purity – which the airport officials had noted down. We had loaned it to the refuseniks intending to retrieve it at the home where I was to sing. But we were apprehended prior. What excuse could we give at customs?

Then I remembered that there was one book they had failed to note down. This was a thin Hebrew-only edition of Kitsur Shulchan Aruch. And so, I hit upon a daring plan. Rather than just write a fake title in English in a Hebrew book which may have looked ‘sus’, I calligraphed the following inscription inside the front cover of the Kitsur volume. To Judith. Trusting you will cherish this Guide to Family Purity all your married life. Never let it out of your sight! Love, Mum.

It was daring because we had been told on one of our pre-departure briefings that a few of the senior KGB agents were experts in the Hebrew language – precisely to make it easier for them to catch a refusenik studying a religious text. However, we figured that most KGB agents were more likely to be well-versed in English than Hebrew. After all, the bureaucrats at the airport had capably recorded the English titles of all our other books. But they left the Kitsur alone – understandably if they couldn’t read the Hebrew title!

Meanwhile, Judith had another concern. It was strictly illegal to take Russian currency out of the USSR and we had therefore surrendered the little we had had. But she had heard a rumour that KGB hid money in the roller blinds of the window carriages to frame those against whom they wanted to make a case. The ubiquitous presence of Russian officials constantly patrolling outside our carriage did nothing to calm her already-frayed nerves.

The train ride through dull and grey landscape was tedious as well as tense. and, what with the frequent lengthy stops, seemingly interminable. We had no idea when we would reach the border. Suddenly at one of the stops there was a flurry of activity. Officials entered our carriage. They checked our documentation. No, we said truthfully, we had nothing dutiable to declare. I said fervent Tehilim under my breath. They talked among themselves at length. We had no idea what they were saying. The tension was unbearable. We were all ready to reach for the books when …. abruptly, they returned our documentation, bid us a cursory unsmiling greeting – and left. Mercifully, the books had been ignored! Five minutes later there was a buzz of excited noise outside our carriage. Finnish staff appeared, smiling, offering us glasses of tea. They told us that we had crossed the border. Thank G-D we were safe! Our relief was immeasurable.

The mood in the train was utterly transformed. Freedom had dawned! Fellow passengers came over to us marvelling at how long the customs officers had stayed with us. They appeared to think we must be VIPs to have experienced such treatment!

During the course of our conversation, it transpired that we were in a new time-zone. Our watches had to be set one hour later. Which presented us with a new major concern. We would be arriving not ninety but just thirty minutes prior to Shabbat – if we were lucky!

We resolved to jump the carriage in Helsinki as the train was about to stop. We had barely twenty minutes to candle-lighting! As we ran along the platform with our luggage to the station exit intent on finding the nearest motel or boarding-house, we were startled to suddenly hear our surname being called. It turned out to be … a member of the British Embassy staff. She told us she realised we would be arriving close to the Jewish Sabbath and had already booked us in to a motel (or pension as she called it) a few streets away.

The British Embassy had come good big time! We now realised that their ‘curtness’ when we had rung them the previous day was, in actuality, a vigilance not to land us in further trouble. They had known the phone would be tapped and, while not saying anything, had noted every word we told them, had read between the lines and, doubtless, made further investigations. Or maybe our story had broken already!

She wanted to walk us there, but we said “no, a taxi please!”. She came with us and checked us in. Meanwhile Judith was turfing out the contents of our suitcase, searching for our small candlesticks, our box of matsa and the grape juice we had brought with us as well as some basic staples. She lit Shabbat candles with minutes to spare. We feasted that evening on tinned sardines and some canned sweetcorn. Shabbat had never tasted more divine!

I davened in our assigned room while Judith spoke at length with the embassy staff member about our experiences. After davening, I asked the receptionist for a map. I was amazed and gratified to see that Helsinki’s main synagogue was a five-minute walk away. I came excitedly to tell Judith – but she already knew! The extraordinarily helpful embassy staffer had informed her.

We walked to shul together on Shabbat morning. Judith recalls me being honoured with an aliya. Then the rabbi spoke (in his native Swedish as he later told us, which is not dissimilar to Finnish). Suddenly our ears pricked up as the words “Leningrad”, “Moscow” and “refusenik” were uttered. It was, we discovered, the very first time the rabbi had spoken about Soviet Jewry from the pulpit. Finland was a neutral country but because it bordered the Soviet Union, its spokesmen and media had to be circumspect. However, the repression against dissidents had reached a nadir and this rabbi had decided to take his courage in both his hands and address it.

The rabbi and rebbetsin invited us for lunch. We recall being in the company of a fascinating, cosmopolitan group of Jews including a furrier from north-west London who, on hearing our story, asked us to contact him following Shabbat. He turned out to be our malach shel chesed, loaning us the airfare to get home. (The 35s whom we contacted at the first opportunity after Shabbat would have wired us the money – as of course would our parents had it been necessary – but this was quicker and easier.)

The earliest flight to be had was not for a couple of days so we enjoyed being tourists in Helsinki. Our most memorable experience was walking on water (the iced-over Gulf of Finland!) We also bought a pair of candlesticks made of Finnish glass to remind us of the sweet taste of freedom following the most perilous escapade of our lives! They have a prominent place in our display cabinet.

**************************

We spoke to our somewhat shell-shocked but mightily relieved parents from Helsinki. My father-in-law advised us “Keep your heads down when you arrive in Heathrow!” As it turned out, we were not approached by any reporters until we arrived back in Newcastle. Evidently in London our “big” story was now already fish and chip paper!

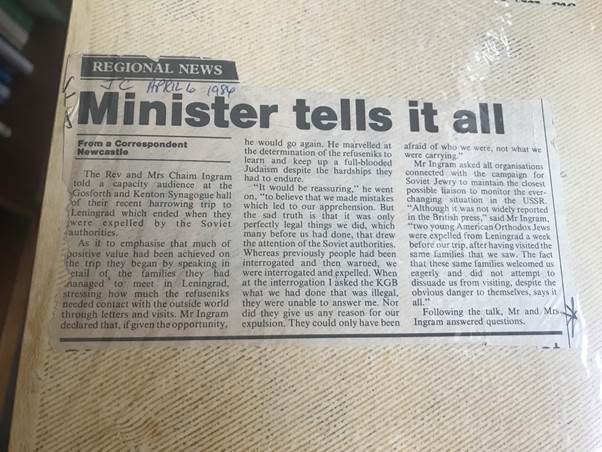

But in Newcastle upon Tyne, it was a different story …!

We were carrying with us, for some reason, a compensation voucher for a first-class British Rail ticket. We decided to use it for our three-hour ride home to Newcastle so that we could stretch out and catch up on some much-needed sleep.

On arrival, we alighted from the train somewhat refreshed and walked towards the exit. Suddenly we heard a noise of rapid motion behind us, and our names being called. This time it wasn’t a British Embassy staffer! It was the paparazzi. They had been waiting for us by the rear third-class carriages! They stuck a video-camera in our faces and started an impromptu interview with us on the station platform. That interview was shown on TV screens throughout the UK and beyond!

When we arrived home our next-door neighbour greeted us excitedly. She told us that reporters had been camped outside our house and had interviewed her. The pressing question they wanted to know was …were we married! Apparently the Tass report had given my wife’s name as Judith Levy (her maiden name) as she had not yet changed her passport. Our sharp-witted neighbour responded: “just look through their front window and you will see their wedding photograph on display!”

In the days that followed, it became evident that the KGB’s strong-armed tactics against us, a young, newly married minister of religion and his wife, was backfiring against them badly. The press coverage was unfailingly sympathetic to us and hostile to the Soviet bureaucrats.

It transpired that the week before our visit, two young American Orthodox Jews had also had their visas cancelled in Leningrad. One day prior to our detention, London-based Mrs. Ann Kennard and her daughter suffered harassment. A few days later, we learned that Dayan Chanoch Ehrentreu of the London Beth Din had shockingly been manhandled by KGB agents. But after our story broke there were no more incidents. Things quietened down again. We like to think that this was due to the fallout for the KGB from the unfavourable press they received as a result of our treatment.

We neither saw nor heard any mention in the news of our adopted refuseniks Pavel Astrakhan, Yitzchak Kogan and Grigory Wasserman. We took it that no news was good news and davened that they and their families were safe from harassment at least for the time being.

********************

As a postscript: a few years later when we were rabbi and rebbetsin in Leicester, a travelling exhibition intended for the wider community entitled The Jewish Way Of Life, spearheaded by the late communal stalwart Ruth Winston-Fox, came to town. One of the exhibits was on Soviet Jewry. We looked on a screen and to our amazement we saw the interview we had given on the station platform being relayed. Which was nothing compared to the amazed looks on the faces of the motley viewers who had one eye on the screen and one on the young couple standing there right next to them!

Scarcely a year after viewing that exhibition, seventy years of seemingly invincible Soviet Communist rule came to a juddering demise.

They, the mighty ones, ignominiously perish – but we, the downtrodden ones, mightily live on!

For in every generation they stand against us to destroy us, but G-D constantly – and miraculously – rescues us from their hands! (Pesach Hagada)

___________________ With grateful and abiding thanks to my father zl for preserving every pertinent newspaper clipping and report he saw in his “scrapbook”, now bequeathed to us.